Critical anthology

The «Painterly Tables» of Eros Bonamini, from the catalogue of the show «Tabelle pittoricho», Lo Scudo Gallery, Verona 1975

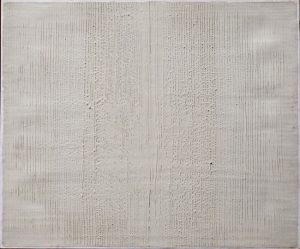

Painting as an open field in which to investigate material enqui-red into with full respect for its own internal aims and needs, and then the elimination of time apartfrom that relative to making the work, familiarity with his means and direct contact with them. these are all fundamental to the research of Eros Bonamini.

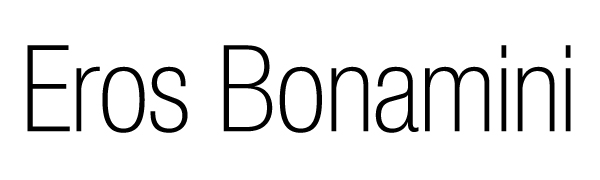

His awareness of the latest «concrete» researches is evident, as is also the case with regard to the specific way of making works, a genuine commitment to an «everyday» method rather than to «noble», «high holiday» or museographic myths. The artist does not permit the work to have any constructive «quality» and eliminates all possibilities for lyrical or ironic «form». Instead he traces out a «map» on which to work by way of va-rious procedures and paths. So we are not dealing just with the negation of the painting as a fixed point, closed in itself in splen-did isolation, but it is within painting itself that it negates itself and proposes itself as the territory and the testimony of an onward-going pictorial process. In such a context it is permissi-ble to believe that there exists a precise ideological awareness, a «behaviour» which is not aesthetic, romantic or vitalistic, but which is «everyday», dressed in working clothes rather than in «artistic» dress. All this promises, obviously, a regression to mi-nimal levels of painting, expressed by eliminating the «field», su-perimposed and manipulated by the descriptive, symbolic and emotional tradition, and a progression instead by repeated con-tact with the material in such a way that it can react according to different parameters.

For this reason I believe that we can never insist too much that «zero degree» painting, reticent with regard to certain illusory pa-radises, can infact offer an extremelyf ull storehouse of news and can enrich itself with meanings and allusions which are anything but silent and deaf to dialogue  On the contrary once a solid base has been established outside neo-romantic vitalism, the actual tendency is that of populating the field of action with an extraor-dinary richness of data.

On the contrary once a solid base has been established outside neo-romantic vitalism, the actual tendency is that of populating the field of action with an extraor-dinary richness of data.

Negating both illuministic certainties and great ideological sy-stems, in the 70s the artist was more drawn to an «empirical» way of working, fed by that basic scepticism which characteri-ses our age.

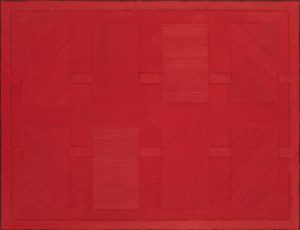

This can be seen in the works of Bonamini, who does not just offer us the results of his research but continues to return to the beginnings of his enquiry, subdividing the field into real «tables» or «schedules» to expressive results.

So nothing is taken for granted, nothing established once and for all. The very praxis of the work becomes critically aware of moving within that immense space caused by the fall of the principle of cause and effect. The knowledge that making and planning exist only in the effective time of actual work produces an analytical meditation of the means employed, whether they be the paint brush, the pallette-knife or any other instrument. Of course this does not rule out the possibility of lyricism or of disturbing perceptions. One sees in Bonamini’s work the powdery or the flattening aspect of white according to the play of light, the flaring up or retraction of black, the subtle vibrations of greeny-grey. But it is not this that inte-rests the artist nor is it the most important fact about the pain-tings. Our attention is always turned to the rhythms and the ways which the material has been called on to express, to that conti-nual return to the field which is characteristic of a way of wor-king which has become a daily job, a tout-court refusal of the overwhelming and «artistic» gesture.

So nothing is taken for granted, nothing established once and for all. The very praxis of the work becomes critically aware of moving within that immense space caused by the fall of the principle of cause and effect. The knowledge that making and planning exist only in the effective time of actual work produces an analytical meditation of the means employed, whether they be the paint brush, the pallette-knife or any other instrument. Of course this does not rule out the possibility of lyricism or of disturbing perceptions. One sees in Bonamini’s work the powdery or the flattening aspect of white according to the play of light, the flaring up or retraction of black, the subtle vibrations of greeny-grey. But it is not this that inte-rests the artist nor is it the most important fact about the pain-tings. Our attention is always turned to the rhythms and the ways which the material has been called on to express, to that conti-nual return to the field which is characteristic of a way of wor-king which has become a daily job, a tout-court refusal of the overwhelming and «artistic» gesture.

On the other hand, in this situation of «work making» there is no reason for the existence of a predominantly visual argument, traditionally considered to be the parameter of modem culture. I am referring to the shock, to the manipulation and the violen-ce, to all that aggressive context for which one’s gaze becomes a landing field within the vunerability of the unconscious. The works in this new situation of concrete art are more concieved than looked at, and when the subject is one of space and light the situation cannot stand aside but must present itself as a men-tal projection to ours in a continual flux between inside and out-side and viceversa: and so the time for reading the work belongs above all to consciousness.

3 December 1974

Magagnato in B. Freddi, L. Magagnato, P.C. Santini et alii, Il materiale delle arti. “Processi tecnici e formativi dell’immagine” (cat. della mostra), Punto e linea, Milano 1981, from the Catalogue of the show «Il materiale delle arti», Castello Sforzesco, Milano 1981

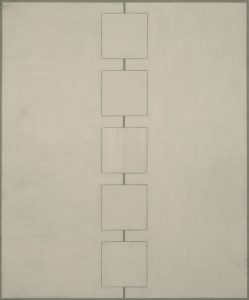

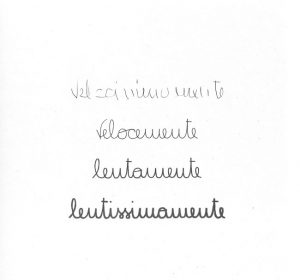

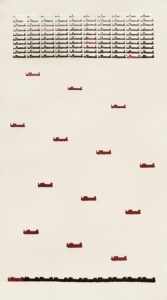

We could say that the primary material of Eros Bonamini is time. We might say better that each artistic action of his is the search for an object in which can be seen something marking the pass-ing of time, measuring its rhythm, its growth and slowness. In Bonamini’s existential experience the passing of time has a particular pregnancy, he waits for the minutes, the hours, the days to pass, together with their heaviness. And in this wait there is almost a sense of impotent inertia which is reacted to with the use of an empiricai metronome to mark, not the accelerations, but the diminution of power, not the forming but the spreading of the mark. He has recently recorded on strips of canvas the marks of a brush which always writes the same short and insig-nifcant words: the configuration of a gesture in ever different forms, according to its increasing duration in time, follows a har-monic development. A thin fine of continuity, a tangible sign of time, indicates a developing process in which in ever increasing time there is dissolved the earlier legibility of a word, a word which finally, loses all traces of iconicity and of comprehension. The marking of time is interwoven with the constancy of the signs, and the support registers the graphic effect of this cross-ing over of situations.

We could say that the primary material of Eros Bonamini is time. We might say better that each artistic action of his is the search for an object in which can be seen something marking the pass-ing of time, measuring its rhythm, its growth and slowness. In Bonamini’s existential experience the passing of time has a particular pregnancy, he waits for the minutes, the hours, the days to pass, together with their heaviness. And in this wait there is almost a sense of impotent inertia which is reacted to with the use of an empiricai metronome to mark, not the accelerations, but the diminution of power, not the forming but the spreading of the mark. He has recently recorded on strips of canvas the marks of a brush which always writes the same short and insig-nifcant words: the configuration of a gesture in ever different forms, according to its increasing duration in time, follows a har-monic development. A thin fine of continuity, a tangible sign of time, indicates a developing process in which in ever increasing time there is dissolved the earlier legibility of a word, a word which finally, loses all traces of iconicity and of comprehension. The marking of time is interwoven with the constancy of the signs, and the support registers the graphic effect of this cross-ing over of situations.

Eros Bonamini has already experimented with variations of forms repeated over a constantly slowed down period of time on many different supports. Beside certain works of this latest peri-od, there have been hung other works with different supports in order to show how the variation of materials does not change the resulting harmonious development of elementary forms towards which his research tends to return. In one case it is the weakening of a scratch to a point where it no longer marks the plaster support. In another it is the intensification of a tone of colour as the strips of fabric immersed in liquid colour acquire the ability to absorb. In vet another case it is the drying out of lumps of soft clay which slowly becomes less and less sensitive to the pressure of the instrument which works on it. With just the right words about this way of working, Bonamini has said, «In my work, the process/work identifcation is complete in that there is attributed to the word no higher value than that of an artifcial product of an empirical nature». I would add, though, that this operation, apparently not an aesthetic one, shows an in-terest in materials that lifts them out of anonimity and has its result a poetical act in the aesthetic sense of the phrase.

a

«Volume» form volvere, turn. It really is the «dark» moment be-tween the passage from one page to another when what has been memorised is absent and there can be seen the two following pages, the individual pages are, then, framments of a continu-ous argument the development of which is limited by the final page, that conclusive solution that might be an unveiling, the resolution of an enigma, but which might also be the opening up of other enigmas. My narration, both when using just one way of writing — the brush and ink injected into the canvas — or when presenting at the same time three means and three writ-ing systems (the alphabet, the fine, the point) accentuates the character of the single episode, all resulting from time differences, the progression used, the making of a scratch or letter, but it must always be seen as part of a continuum. The single page is then an instantaneous observation of modifications which have oc-curred, or, in other words, of the «figure» which the time em-ployed in its making has determined but which also, at the same time, refers back to the moments preceding the hypothesis which indicate what can happen later. So the page is then a «pause» in the continuum of the procedure, that can be followed in the normal left to right way of writing but, just because of its quali-ty as a «figure», suggests spatial readings and dismantles and recomposes the main direction.

From the Catalogue of the show, «Arte nel Veneto 70-80»

Fondazione dell’Opera Bevilacqua la Masa e Ca’ Pesaro, Venezia 1982

a

Caramel, Una coerenza non preconcetta, in L. Caramel, E. Miccini, A. Veca (a cura di), Eros Bonamini. Cronotopografie 1974-1993, Adriano Parise Editore, Verona 1993, pp. 9-11

I have followed Eros Bonamini since in the early sevenies he began to involve himself with those analytical operations of the painting of painting which open this volume. The consideration of each individual moment of his career has, as the result of a kind of shortsightedness, made it difficult for me to perceive simultaneously its overall complexity and variety. His work has of course been undertaken within certain parameters, but these have facilitated the impression of continuity rather than of development.

I have followed Eros Bonamini since in the early sevenies he began to involve himself with those analytical operations of the painting of painting which open this volume. The consideration of each individual moment of his career has, as the result of a kind of shortsightedness, made it difficult for me to perceive simultaneously its overall complexity and variety. His work has of course been undertaken within certain parameters, but these have facilitated the impression of continuity rather than of development.

I think that this inevitable mechanism has influenced other of his admirers, but from this presentation of over two decades of his work they will, as in my case, find the stimulation for a complete re-examination: one that avoids, of course, the danger of superimposing an «after» on a «before», but which at the same time allows the formation of judgements on the basis of a wide representation of the varied phases he has passed through.

When I first saw the «marks-traces» in cement which progressively solidified, and later the series of tapes soaked in hydrogen peroxide over different periods of time I thought – even more than for the immediately preceding paintings based on the differences born from varied layers of paint, on a homogenous field – I was seeing one of those analytical-conceptual «cool» choices which were the heredity of Bonamini’s generation

Just as those artists working a decade earlier could not help but be influenced by Abstract Expressionism, even though it was already in decline, so the artists being formed half way through the sixties could not avoid, however minimally, the climate of mental rarifaction in reaction against the implosion-explosion of the preceding gestuality, as well as against the objectuality and objectivity which continued to exist at the end of the 1960s (in Italy at least; elsewhere the inversion of tendency was felt halfway through the 50s).

so the artists being formed half way through the sixties could not avoid, however minimally, the climate of mental rarifaction in reaction against the implosion-explosion of the preceding gestuality, as well as against the objectuality and objectivity which continued to exist at the end of the 1960s (in Italy at least; elsewhere the inversion of tendency was felt halfway through the 50s).

It was a tendency which ended up without a possible exit, in a cul de sac, which at this distance in time is quite apparent. The point of arrival could only be the death of art, not just of a historical phase as has often happened. The seductive ghost of Duchamp could lead, did in fact lead some, to the complete refusal of that resolution in a concrete form which has always been the property of art. The work of Bonamini in the 70s, above all that of the «peroxided» and stained tapes, could be seen to be closed in this dimension. And in fact what was seen was a radical experimentation of phenomena in themselves, just as might happen in a physics or chemistry laboratory, in order to investigate the physical and chemical characteristics both of compositional and conditional changes of the material.

Of course these components were dominant. As Veca notes in this book, the artist was experimenting with the «relativity» of the tools and with results which were a direct testimony and not interfered with by the working process. The very catalogue-like, serial organisation of the results of his analyses pushed the works towards direct knowledge and exposition of their own formative process which had the planning characeristics not only of objective research, but of an inventive and expressive proposal (of an expression that was not just that, tautologically, of the thing or of the experiment in itself).

What Bonamini has since produced helps us to see the importance, even in his most extreme works, of the making process: within an analytical context, certainly, as has already been said, but with its own interior power. Veca was happy in choosing «Traces of making» as title, underlining, for the «tapes» too, the importance of that component, quite apart from the experimental aims or objectives. Making, too, as a vital act, vital in the sense of living, and thus – however elmentary and without complications of meaning – as expression. Within the concrete weave of the phenomenon, of what is contingent, where – as Eugenio Miccini in the text published here has pointed out – time and space are those of making and of thinking, the measure and the place of the event. He continues by saying that in this empirical time, created by spatial events, Bonamini leaves behind traces, or better, a trace, linking the syntagms into a structure.

What Bonamini has since produced helps us to see the importance, even in his most extreme works, of the making process: within an analytical context, certainly, as has already been said, but with its own interior power. Veca was happy in choosing «Traces of making» as title, underlining, for the «tapes» too, the importance of that component, quite apart from the experimental aims or objectives. Making, too, as a vital act, vital in the sense of living, and thus – however elmentary and without complications of meaning – as expression. Within the concrete weave of the phenomenon, of what is contingent, where – as Eugenio Miccini in the text published here has pointed out – time and space are those of making and of thinking, the measure and the place of the event. He continues by saying that in this empirical time, created by spatial events, Bonamini leaves behind traces, or better, a trace, linking the syntagms into a structure.

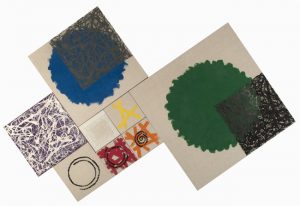

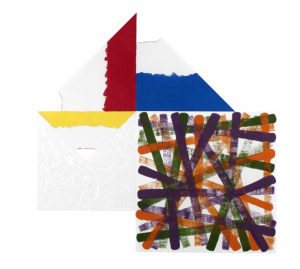

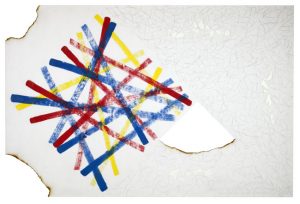

This is most evident, among the earliest works, in the cement pieces, and it was to be heightened in the 80s with the softening of his previous minimalistic tendency and his adoption of colour and of freer, more casual techniques, even though still highly controlled (the paint was still «absorbed» with the help of felt-tipped pens, wads of cotton, sirynges – this allowed a particular diffusion of the colour on the surface which was again, at times, of canvas). His «paths» – spiral, labyrinthine or whatever – were fixed by the colour-mark and by aggregation, paratactical or more complexely articulated, by other surfaces treated differently.

The results were such as to stimulate Miccini to say that these labyrinths or spirals, however much deprived of their symbolic or mythological allusions, refer each grapheme, each moment, back to itself and to a continual allegory of life, all leading to a story in which, differently from myth, there are no amnesias, but where everything is present in realtime.  This, he says, is also a metaphore for existence. I too think this is true, above all for the recent «cronotopographies», so free yet controlled, not emotional, yet vibrant with a lucid and lyrical burden. So much so as to risk underestimating those analytical components which, however dijfferently presented, remain primary. And here the whole career of Bonamini recommends a change of viewpoint. If what the artist has done since the analytical paintings, the cement pieces, and the tapes helps us to understand better his early works, these works must be taken into consideration in order not to forget that constant of planning systemacity and of formal and chromatic investigation which remains, as I have just said, essential. Just as essential and primary remains, with regard to the results of which it is the trace, the working process. And not just at a theoretical or methodological level, but, as I said earlier, as the expression of making. From this there is also derived the singularity of Bonamini in the present art scene: he is noi only outside fashions, as Miccini reminds us, but also outside styles or trends. Eros too, like all of us, carries the marks of the culture he inherited but not as a dead weight. Rather as the roots which give life and character to the blooms that year after year flow in the diversity of a non-preconceived coherence.

This, he says, is also a metaphore for existence. I too think this is true, above all for the recent «cronotopographies», so free yet controlled, not emotional, yet vibrant with a lucid and lyrical burden. So much so as to risk underestimating those analytical components which, however dijfferently presented, remain primary. And here the whole career of Bonamini recommends a change of viewpoint. If what the artist has done since the analytical paintings, the cement pieces, and the tapes helps us to understand better his early works, these works must be taken into consideration in order not to forget that constant of planning systemacity and of formal and chromatic investigation which remains, as I have just said, essential. Just as essential and primary remains, with regard to the results of which it is the trace, the working process. And not just at a theoretical or methodological level, but, as I said earlier, as the expression of making. From this there is also derived the singularity of Bonamini in the present art scene: he is noi only outside fashions, as Miccini reminds us, but also outside styles or trends. Eros too, like all of us, carries the marks of the culture he inherited but not as a dead weight. Rather as the roots which give life and character to the blooms that year after year flow in the diversity of a non-preconceived coherence.

Milan, February 1993

a

E. Miccini in C. Cerritelli, E. Miccini (curators), Eros Bonamini. Il labirinto della pittura (catalogue of the exhibition held at Monte Ridolfi (FIorence), Meta Edizioni, Rome 2001

Dear Eros, thumbs-up! Prometheus, perhaps the most human figure of classical mythology, though also the symbol of rationality and creativity (together with Athena; without a doubt Giusi), has set your space alight.

Dear Eros, thumbs-up! Prometheus, perhaps the most human figure of classical mythology, though also the symbol of rationality and creativity (together with Athena; without a doubt Giusi), has set your space alight.

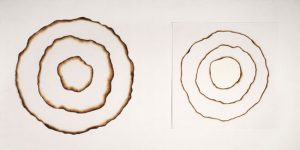

Fire burns and consumes, it destroys the material but not the form, in other words it leaves a trace. And this trace is a mark and as such it obeys the length of time you have stolen from Chronos.

When writing about your work, I once commemorated the marriage (though I really should say the Saturnalia) celebrated in your rooms between space, which is the measurement of what is not there, and time, which is the measurement of its duration.

But we can be bacchanalian about what only the gods can do. As we know, humans, or rather artists, the sons of Titan, have abstract bacchanals: they put form, measurement, structure, and colours in the place of things.

For example, when you regulate the temporal successions in the visible structure of a spiral you invent – how can I put this? – an affinity, a simile, between temporal development and spatial development. However, the dominant form in these analogies is not only a spiral but the infinite (diagonal or bisecting) sections of quadrilaterals, or of circles (rays), or else all possible segments (crosses, parallels)…

So what seems to me to be new in this latest research of yours that you will be showing in Florence is, in the meantime, this consideration of mine about your work, something that I had not glimpsed when I wrote an essay about you some years ago. And then there is your recent discovery of fire.

But there is still more: a certain lowering of sensuality, that should not be blamed on our age but, rather, on a kind of “deconstruction”, of an evidently symptomatic renunciation of colour:  from the colour range to the white that all colours contain; from the tremendous colouristic violence of fire to its resulting reduction; from the unpicking of the rainbow to the black of its negation. If there were still something left to be expelled from a colour-range that is not without a certain fascination, then you have tried to do so. But, as so often happens, this is something you cannot get rid of. I am alluding, with reference to just two recent works, to a certain use of tonality that is not Morandi-like but, on the contrary, is rough and that layers blacks, greys, and ochre together with burnt edges to provoke a different kind of enticement. But the victory of Saturn, the grand old man with a white beard and an hourglass, resists.

from the colour range to the white that all colours contain; from the tremendous colouristic violence of fire to its resulting reduction; from the unpicking of the rainbow to the black of its negation. If there were still something left to be expelled from a colour-range that is not without a certain fascination, then you have tried to do so. But, as so often happens, this is something you cannot get rid of. I am alluding, with reference to just two recent works, to a certain use of tonality that is not Morandi-like but, on the contrary, is rough and that layers blacks, greys, and ochre together with burnt edges to provoke a different kind of enticement. But the victory of Saturn, the grand old man with a white beard and an hourglass, resists.

His son, the fearsome Jove, expelled him from Olympus though, given that he was immortal, this was probably a waste of time. But Prometheus, who had not only deceptively stolen fire but had taken first place in the creation of the universe and had been punished by Jove with … an aching liver, was pardoned. After all, mythology too has its rules: how can you punish someone who invented … man?

Dear Eros, these are some of my off-the-cuff thoughts.

We will talk further at your show in Florence.

All the best and good luck with your work.

Eugenio Miccini

a

M. Bertoni, Per Eros Bonamini, presentazione della mostra Eros Bonamini. Cronotopografie: A-Ulì-Ulè tenuta a Immobilia, Verona, 2001

Cronotopografie. Cronotopografie. Eros Bonamini has been working around this concept for twenty-five years, with perseverance (if not obsession) and fidelity that make us consider his production as an immense, unique “artwork” whose single “paintings” are the paragraphs and the compositional cycles (coats, cements, tapes, absorption,…) are the chapters.

Cronotopografie. Cronotopografie. Eros Bonamini has been working around this concept for twenty-five years, with perseverance (if not obsession) and fidelity that make us consider his production as an immense, unique “artwork” whose single “paintings” are the paragraphs and the compositional cycles (coats, cements, tapes, absorption,…) are the chapters.

Cronotopografie: Eros Bonamini has been working around this concept for twenty-five years, with perseverance (if not obsession) and fidelity that make us consider his production as an immense, unique “artwork” whose single “paintings” are the paragraphs and the compositional cycles (coats, cements, tapes, absorption,…) are the chapters.

Cronotopografia: literally, writing of time and space. Coldly, the term says less than what “picture” and artwork imply, because the hidden tension that the term does not show is the one that forces time and space to reveal painting, a planned-painting in the sense and within the limits of a time and space defined in reasonable quantities that yearn for measure, proportion, “size”. Nevertheless here already, the path that might seem simple, linear and consistent, reveales discrepancies and incongruities. The number that fixes the time and the space of the pictorial action is an approximation, a model which sets out the how much and not the how, to use an entirely relevant expression, since all Bonamini’s work is in the field of aniconic researches, a grill-score whitin which he makes shapes and colors resound. Incidentally, this recall is not only important as an highlight of the very close relationship between visual arts and music all over the century, or of the equivalence between proceeding with lines, colors and volumes and the one with notes, rhythms and pauses, but above all it is important as the accentuation of the sonorous potential (though latent and unintended) in the artwork, which approaches for opposition, after the necessary distinctions, to that of Daniele Lombardi, who, starting from music, reaches visual phantasmagoria, perspective sketches of sound constructions.

Cronos and topos, time and space, or even: cronotopa “dimension” of painting, meaning condition in motion of the painting that is beeing done.

Poieticamente. This “dimension” (in the sense of “level of pictorial reality” with its time-space coordinates therefore its features and specific peculiarities) that Bonamini’s painting sets up requires more than a clarification. Firstly, Bonamin’s cronotopo has nothing to do with either, “memory” or sequences (past, present and future). This implies a kind of indifference to styles, tradition and even the formal influences, but also an original imprint compared to those experiences that made ephemeris time central instrument and matter of pictorial research (Opalka, On Kawara). Because, Bonamini’s concern is the urgent intervention that is consumed (and physically burns) here and now, without before or after, and that wants to expand through successive contemporaneity according to a sort of eternal present, or of eternal return: it may be a sign performed in the voracity of a race against time, and it may be a pattern made of a slow meditative calm.

So then Bonamini’s cronotopo has the value of a musical metronome and his painting has the value of the theme variations of Bach or Philip Glass ones; here also the persistence of the spiral shape as a figure of a place and a time that tend to infinity (with the consequent jump from “measuring” to “dimension”), even if in the precarious nature of the action and the imposed limits, or perhaps, precisely due to this.

If these are the premises, you will have to take some of the reasons of Bonamini’s poetics. When, at the beginning, it is said of a hidden and felt tension, now we are able to clarify and specify it. We are, in fact, in the presence of an art who lives thanks to the contrast between the ruptures of the different cronotopi and the continuity of the spiral; between the finiteness of each painting and the infinite of the spiral: in order to say that every picture or painting frame finds its alterego in the opera omnia, in everything seamlessly produced by the artist; in order to say that the fragment yearns to integrate with the totality, while continuing to be a fragment, a part. If the latter is hopelessly bound to its status, the work is full of a breath that is not given by the sum of the pieces composing it. If one finds perfect coincidence between the time and space necessary to its execution and the time and space naming and defining it, the other lives in doubt and the doubted thing, in that “opacity” (saying it as Miccini and Jakobson) that holds the mind on the magnificent absence of truth.

If these are the premises, you will have to take some of the reasons of Bonamini’s poetics. When, at the beginning, it is said of a hidden and felt tension, now we are able to clarify and specify it. We are, in fact, in the presence of an art who lives thanks to the contrast between the ruptures of the different cronotopi and the continuity of the spiral; between the finiteness of each painting and the infinite of the spiral: in order to say that every picture or painting frame finds its alterego in the opera omnia, in everything seamlessly produced by the artist; in order to say that the fragment yearns to integrate with the totality, while continuing to be a fragment, a part. If the latter is hopelessly bound to its status, the work is full of a breath that is not given by the sum of the pieces composing it. If one finds perfect coincidence between the time and space necessary to its execution and the time and space naming and defining it, the other lives in doubt and the doubted thing, in that “opacity” (saying it as Miccini and Jakobson) that holds the mind on the magnificent absence of truth.

Bonamini’s pictorial cronotopo is the methodological tool that allows you to simultaneously play all the instruments, to use all the languages “in concert” (sign and writing), it is what is left to the man when he has even forgotten the memory (the real one as the historical one), in a never tamed anxiety, never satisfied, never in peace, as he has so brightly explained: “what is interesting is the darkest moment of transition from one page to another, when what you have stored is absent and you can see the development in the next two fronts. The individual pages are then fragments of a continuous speech whose development finds its boundaries on the final page, in the final solution that can be disclosure, riddles resolution, but it can also open, so to speak, other enigma…Then the page is also a break in the continuum of the process, which can be travelled in the trend of usual handwriting but which, thanks to its qualities as a figure, suggests spatial readings, decomposing and enriching the main trend”.

a

Excerpts from G. Di Genova (a cura di), Storia dell’arte italiana del ’900. Generazione anni Quaranta. Tomo primo, Edizioni Bora, Bologna 2007, pp. 128-129, 607-609

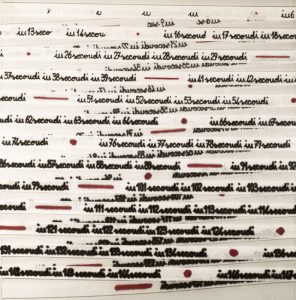

(…) Also the Veronese artist Eros Bonamini strives for a denial of the framework; in the mid-seventies he revised and corrected in his own way the typical procedures of Informal art, such as the poetry of fragment, the one of the wall and the “segnismo” itself, working with iron or wood point or pencils on plasters on canvas (prepared by himself with cement and adhesive glue) in order to obtain signs-traces of different connotation, through interventions timed in seconds or minutes, according to the operational fields, which are sometimes of 50×50 cm, other times of 30×150 cm and often combined in triptychs to highlight the rhythmic differences obtained to a greater or lesser extent, because of the mortar hardening over the time (7). Bonamini defines these works Cronotopografie for the union of temporality, space and signs-traces with strong scriptural connotations, for the implication of the recurring re-emerging of the line, which leads him to column writing, especially in the following decade when he adressed to the blotting papers, according to the operational times: “in 10 seconds”, “in 20 seconds”, “in 30 seconds”, and so on. This kind of writing will find its “ubi consistam” in the artist talk in the following decade.

(…) Also the Veronese artist Eros Bonamini strives for a denial of the framework; in the mid-seventies he revised and corrected in his own way the typical procedures of Informal art, such as the poetry of fragment, the one of the wall and the “segnismo” itself, working with iron or wood point or pencils on plasters on canvas (prepared by himself with cement and adhesive glue) in order to obtain signs-traces of different connotation, through interventions timed in seconds or minutes, according to the operational fields, which are sometimes of 50×50 cm, other times of 30×150 cm and often combined in triptychs to highlight the rhythmic differences obtained to a greater or lesser extent, because of the mortar hardening over the time (7). Bonamini defines these works Cronotopografie for the union of temporality, space and signs-traces with strong scriptural connotations, for the implication of the recurring re-emerging of the line, which leads him to column writing, especially in the following decade when he adressed to the blotting papers, according to the operational times: “in 10 seconds”, “in 20 seconds”, “in 30 seconds”, and so on. This kind of writing will find its “ubi consistam” in the artist talk in the following decade.

It is evident that at the basis of Bonamini’s research lies an operational-existential mania. It is as if Eros wanted to measure the time of making a work (his work), embodied of aesthetics thanks to the rhythmic and weavings of signs-traces, to the visual variations and the cromovisual iridescence, as in N° 90 canvas ribbons simultaneously soaked in peroxide at 130 volumes – N° 30 at 70 volumes – N° 30 at 10 volumes, successivesly immersed in black ink, one every 3 minutes, artwork of 1977 (8). In this measurement of time and in the effects obtained calculating operating times, Bonamini reveals the soul of the work itself, in a sort of operative “x-ray” not lacking conceptual foundation. (…)

(…) It would seem that the Veronese Eros Bonamini, come to writing after researches in the field of abstract expressionism and of an empirical investigation of colors, brought back to the “concrete painting” by Magagnato (77), in the above mentioned Cronotopografie (78) wanted to restart from the rods once used to train children in primary school to control hand in preliteracy activities. In a way it was a conceptual gesture still full of informal memories due to drafts textural concrete plaster supports, which certainly combined the informal poetry of the wall and articulation of space, though differently from Paolini’s Geometric drawing namely for the time calculation of his topographies of signs, with strong scriptural components that are sure to arise in relation to “linearismi” at times curved for vibration from a circle (Sign-trace with felt-pen on canvas in 1 2 3…seconds, 1980), other times at the base of progressively multiplied and numbered vertical axes (Cronotopografie, 1981), where a red serpentine wriggles on, which will return the year after, frayed in Cronotopografie – from 10 to 450 seconds with relative didactic table into 15 horizontal segments, numbered and scanned. If the white of concrete and the black of signs structured the work in 1975 Cronotopografie, here black and red are on the white support, ranging from canvas to paper towels, as it is mentioned in the artwork of 1980 and others, among which the three series of Signs-traces with felt-pen in 5 10 15 seconds (Cronotopografie, 1982).

Undoubtedly everything Bonamini entrusts to the surface should be brought back to writing.

He confirms that in 1982, stating: “My tale, whether using a single means of writing, felt-pen or ink injected onto the canvas, or presenting simultaneously three means and three writing systems (alphabet, line, point), highlights the character of the single episode, played on different progressive time used, in drawing the graph or the letter; but it also must be caught as part of a continuum. The single page becomes immediate observation of the modification occurred, in other words the ‘figure’ that the time employs in determining it, but at the same time it refers to the necessary moments preceeding the hypothesis of what will later happen. The page is also a ‘break’ of the continuous of the process, which can be covered in the usual right-handed way of writing but which, thanks to its qualities as a ‘figure’, suggests spatial reading, composing and enriching the main trend”(79).

The insistence on a terminology more as writer (tale, writing, alphabet, point, graph, letter, page, reading) than as a painter (figure, but in brackets) can be noticed. In fact paper or canvas, both expanse and pleated (like that of Cronografie of 1982 in 12 areas with signs-traces-paths in each front=back in 30 60 90 seconds, as well as the decorative Cronotopografie-nomenclatura of 1983, which hold his interventions, even when they are not numeric or alphabetic) are pages, both single and multiple, for a writing, now of signs, more or less controlled, now gestural with dripping, now painterly, now of the color, which should be read from left to right even when opened in unifications of signic pages, with white covering bands, in monochrome both white and light-blue, and in the larger canvas dabbed in black to determine squares enrolled in other squares collapsing one into another like a vision into a chasm (Cronotopografie, 1989-95 (80)). There is always a bigger canvas (and I was writing page), which is bottom right, as it is also for the 8 canvases of Cronotopografie of 1995, where the largest canvas is moved by blacks filaments of dripping that reminds Pollock (81).

In fact paper or canvas, both expanse and pleated (like that of Cronografie of 1982 in 12 areas with signs-traces-paths in each front=back in 30 60 90 seconds, as well as the decorative Cronotopografie-nomenclatura of 1983, which hold his interventions, even when they are not numeric or alphabetic) are pages, both single and multiple, for a writing, now of signs, more or less controlled, now gestural with dripping, now painterly, now of the color, which should be read from left to right even when opened in unifications of signic pages, with white covering bands, in monochrome both white and light-blue, and in the larger canvas dabbed in black to determine squares enrolled in other squares collapsing one into another like a vision into a chasm (Cronotopografie, 1989-95 (80)). There is always a bigger canvas (and I was writing page), which is bottom right, as it is also for the 8 canvases of Cronotopografie of 1995, where the largest canvas is moved by blacks filaments of dripping that reminds Pollock (81).

And if in the individual “pages” Bonamini also comes to engrave with pyrography the mirrored plexiglass surface, sometimes piercing it as to obtain Braille writing effects (Cronotopografia-Vanitas, 1999), now engraving it with dotted circular concentric paths (Vanitas-Cronotopografie, 1999 (82)), in other cases Bonamini attains the combinations of the three “writing” systems on a single canvas, getting unions of signic handwritings in spiral, circle, tangle or articulated with short brushstrokes and geometric structures, reached through space compartments (Cronotopografie, 1994).

And by continuously writing stories of signs and painting on pages and pages, single or multiplied, even our Veronese artist has managed through calculated execution times in the space of the page to make a book-artwork of 24 pages, articulated as a squeeze-box (as it had been for Volumen in 1985 (83)), true summa of his pictorial-written lexicon which originally derives from “segnismo”, geometry, dripping, weavings, traces and chromatic taches (Cronotopografie, 1997). (…)

a

M. Meneguzzo, L’equilibrio degli opposti, in I. Bignotti, M. Meneguzzo (curators), Eros Bonamini. Panta rei (exhibition catalogue of the show held in Hamburg), Colpo di fulmine edizioni, Verona 2009

One of the most efficient methods for showing something in art – a material, an object, a concept, even a story – is to juxtapose contrasting elements, distant poles that apparently cannot be brought together but yet have some secret link that, once established, highlights the individual factors. Some examples: black and white, the red triangle that breaks the white circle of El Lissitzky’s revolutionary manifesto, or even the centaurs and men of Phidias’s Parthenon metopes – men versus animals – or the Rape of Proserpina by Bernini where opposites are excessively multiplied – man/woman, old age/youth, beauty/ugliness, desire/repulsion, and so on -. The cases are endless and it could almost be said that in every work of art these oppositions are to be found, whether hidden or not. For instance, the examples I have just mentioned purposely show a “scale” of increasing complexity, where in the first case – black versus white – the opposition is not only clearly visible, but is in fact the whole essence of the juxtaposition, while in the last – Pluto and Proserpina – the oppositions are hidden behind the story, the figure, and behind their very number which, as I have pointed out, is multiplied and complicated and takes on complex symbolic and visual meanings.

One of the most efficient methods for showing something in art – a material, an object, a concept, even a story – is to juxtapose contrasting elements, distant poles that apparently cannot be brought together but yet have some secret link that, once established, highlights the individual factors. Some examples: black and white, the red triangle that breaks the white circle of El Lissitzky’s revolutionary manifesto, or even the centaurs and men of Phidias’s Parthenon metopes – men versus animals – or the Rape of Proserpina by Bernini where opposites are excessively multiplied – man/woman, old age/youth, beauty/ugliness, desire/repulsion, and so on -. The cases are endless and it could almost be said that in every work of art these oppositions are to be found, whether hidden or not. For instance, the examples I have just mentioned purposely show a “scale” of increasing complexity, where in the first case – black versus white – the opposition is not only clearly visible, but is in fact the whole essence of the juxtaposition, while in the last – Pluto and Proserpina – the oppositions are hidden behind the story, the figure, and behind their very number which, as I have pointed out, is multiplied and complicated and takes on complex symbolic and visual meanings.

As an artist, Eros Bonamini does not avoid, and does not want to avoid, this kind of construction: on the contrary, he makes it his main centre of interest. What else are his Cronotopografie (the title of all his works, an avant-garde affectation that, with its techno-philosophical definition, involves space and marks) if not a demonstration of secret relationships, brought to light as a result of juxtapositions, conflicts, the “battle of opposites”?

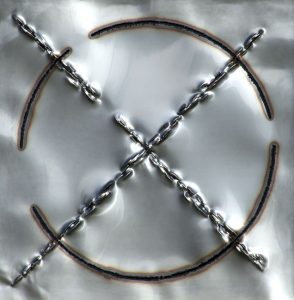

A sheet of steel that mirrors, the basis of all his work, is cut and marked by a blowlamp or laser with simple yet archaic marks: a cross, spiral, line, circle…; the purity of the material – and what is tougher or colder than a material that repulses images by reflecting them? – is violated and burned by a violent action, the result of which is a kind of open wound corroded by the shiny material. The conjunction of such opposite elements makes them more powerful rather than annulling them, it exalts them instead of repressing them.

On that “scale” of complexity I mentioned earlier, Bonamini’s artistic action is far closer to simplicity: there are few elements in play, minimal marks, no narrative to disturb perception, very little symbolism, the greatest clarity  all coherent constructive factors that lead straight to a creativity marked by its extreme conceptual simplicity and precise visual lucidity. There is no doubt that Bonamini comes from the great school of abstraction, and it is just as certain that this is vindicated and confirmed by the artist: for Bonamini that model still has a lot to say, without linguistic hybridisations, metaphorical superimpositions, or narrative “crutches”. The simplicity of the form reflects the clarity of the hypothesis behind it.

all coherent constructive factors that lead straight to a creativity marked by its extreme conceptual simplicity and precise visual lucidity. There is no doubt that Bonamini comes from the great school of abstraction, and it is just as certain that this is vindicated and confirmed by the artist: for Bonamini that model still has a lot to say, without linguistic hybridisations, metaphorical superimpositions, or narrative “crutches”. The simplicity of the form reflects the clarity of the hypothesis behind it.

For this reason, his art is always simple, even though at times he adds to it a colour, a heightening of the material, a three-dimensional risk. However, the final composition never becomes artificially more complicated, darker, more initiatory. Everything is out in the open; it is on, and only on, the surface that everything he wants to say is coagulated: paradoxically, even though experiencing (and being aware of) an art world where the context is becoming increasingly important, Bonamini’s art is one that has the least need of it, and insists that the eye never wanders too far off but is always led back to the surface, absolutely and cogently in the “here and now”.

In this sense Bonamini has coherently retrieved the “tradition of the new” that has freed art (painting above all: and I would, despite everything, define Bonamini’s work precisely as “painting”, just as I would define all Burri’s work as painting…) from any kind of superfluity, and that has descended the steps of a hypothetical artistic “table of elements” in order to reach those indivisible elements that form the grammar and syntax of painting’s language; and from these elements, and from them alone, it has created the constitutive nucleus of Modernity. In this way, despite a vague anachronistic feel of that “Cronotopografie” definition (we no longer live in modernity but in something that comes after…), it cannot be doubted that Bonomini’s use of the term has clearly stated the problem his work deals with, which is not, as we might at first think, only that of material (“topos”, meaning “place” but that we could also interpret as “surface”), but also that of gesture (“grafia” or “handwriting”) and therefore of time (“crono”). The material surface conserves the marks and thus the memory of time, of what was “before” his intervention, and that saw the detached presence of such subjects of the work as the surface, the artist who moves the flame, and the project that foresees a possible effect; of a “during” that is literally lacerating, and of an “after” that is the outcome, the work itself.

Such a concentration does not need anything else; we could even say that this conjunction of elements on the same plane (and I mean “plane” at a conceptual level and also literally the plane of the surface) leads to continuous repetition (but then, Fontana had done the same thing…), and that anyway this repetition is not discursive, as it might be in a conceptual work of art, but necessary, because each time it is formally “different”. And for this type of work form is essential.

June 2009.